Internal Collusion: Forensic Auditing Strategies

Collusion can collapse companies from the inside. At Duja Consulting, we’ve published a new paper that unpacks how internal collusion undermines governance, and how forensic auditing can stop it in its tracks.

Whether you’re a corporate executive, internal auditor, or board member, this guide will show you how to:

- Detect the early signs of internal collusion.

- Investigate through forensic audit methodologies.

- Respond effectively using South African governance frameworks.

- Build preventative controls aligned with King IV and the Companies Act

Plus a case study showing how a listed South African firm uncovered and addressed collusion.

Introduction

Internal collusion – the secret cooperation of two or more insiders to defraud or mislead an organisation – represents one of the most insidious fraud risks in business today. By its nature, collusion can bypass standard controls and remain hidden until significant damage is done. Forensic auditing has emerged as a vital tool to identify such covert schemes and address them decisively. Unlike routine financial audits focused on fair reporting, a forensic audit is an investigative deep-dive into records, transactions, and controls, aimed at uncovering irregularities like fraud, corruption, or mismanagement. It gathers evidence to a standard suitable for legal proceedings, making it invaluable when dealing with collusion among employees or between staff and external parties. In South Africa’s corporate governance context, frameworks such as the Companies Act and King IV emphasise transparency, ethical leadership and accountability, which align with proactive forensic auditing. Notably, shareholders in South Africa have the right under the Companies Act to request a forensic investigation if they suspect fraud or mismanagement, underscoring the expectation of diligence in rooting out internal fraud. King IV similarly calls on governing bodies to implement robust fraud risk management frameworks that prevent, detect and respond to incidents of fraud and corruption.

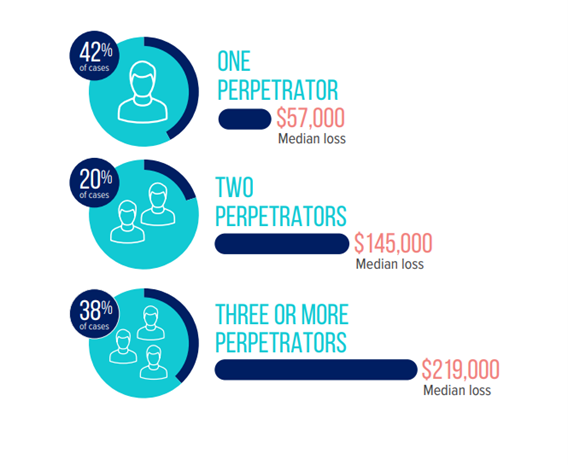

The urgency of tackling collusion is evident in global fraud trends. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) reports that a growing share of occupational fraud involves collusion: 58% of cases analysed in 2022 involved more than one perpetrator, up from 42% a decade earlier. Collusive schemes also tend to inflict greater losses – one study found frauds with two perpetrators caused median losses over twice as high as those with a single perpetrator.

Figure 1:

ACFE data illustrates how fraud losses escalate when multiple perpetrators collude, compared to lone-actor schemes.

For executives and directors, these facts are a wake-up call: the threat of internal collusion is real across all industries, and vigilant measures are required to combat it. This paper provides a comprehensive guide on how to detect collusion through forensic auditing, how to investigate and respond to such incidents, and how to strengthen controls to prevent recurrences. A real-world case study is included to illustrate these principles in action. The discussion is framed in practical, professional terms for a corporate management audience, reflecting South African governance standards (e.g. King IV, Companies Act) and ACFE best practices.

1. Detecting Internal Collusion

Detecting collusion can be challenging because cooperative perpetrators can cleverly circumvent segregated duties and other checks. Even the most well-designed internal control system ultimately relies on employees to act honestly at their point of responsibility. When two or more employees conspire to override controls, red flags may be subtle. Therefore, organisations must employ both preventive and detective measures to spot collusion early. Common detection methods include whistleblower tips, data analytics, internal audits, and management reviews, often used in combination.

Whistleblowing and Red Flags:

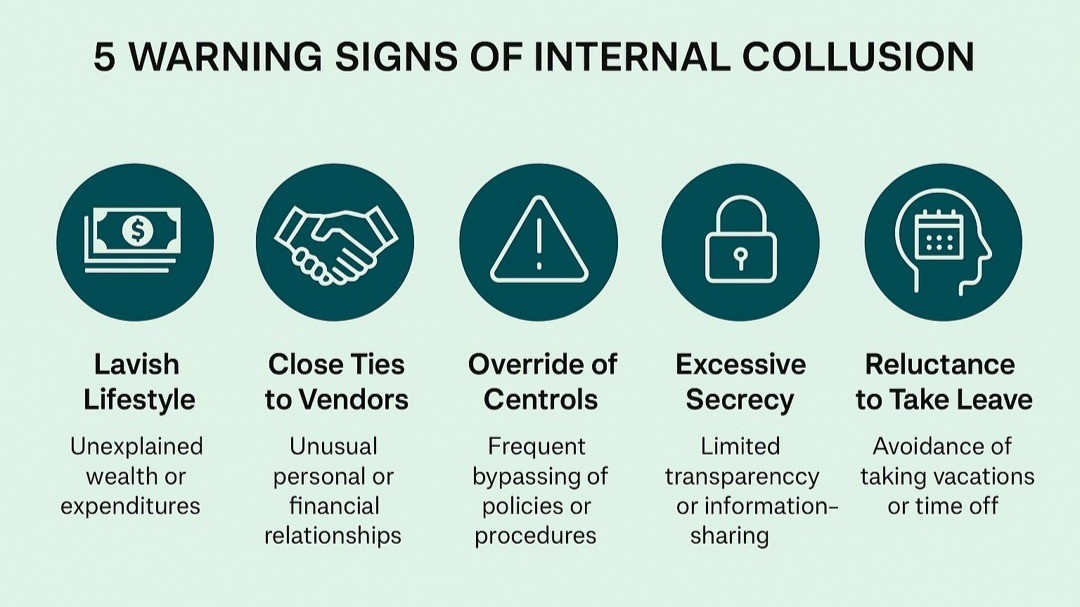

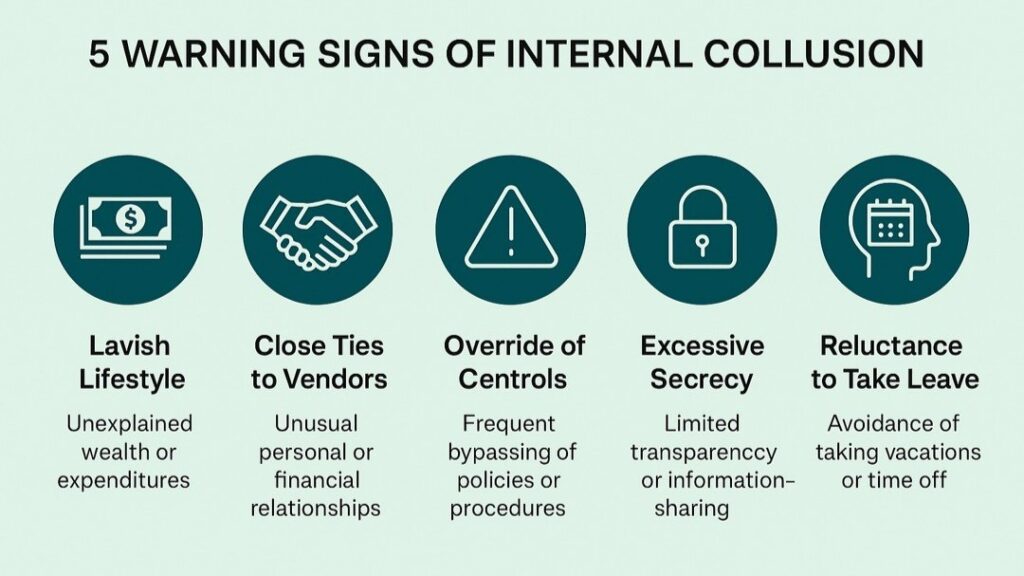

According to the ACFE, tips are by far the most effective means of fraud detection, accounting for 42% of cases detected – more than twice the rate of detection by internal or external audits. Employees are the source of over half of such tips, which highlights the importance of cultivating a speak-up culture. South Africa’s Protected Disclosures Act protects and encourages whistleblowers to report wrongdoing without fear of retaliation. President Cyril Ramaphosa, in endorsing whistleblower protections, noted that “whistleblowing is an essential weapon in the fight against corruption” and vital for exposing collusive fraud schemes. Organisations should therefore ensure accessible, confidential reporting channels (e.g. hotlines, online portals) and actively promote them. The presence of a hotline alone has been shown to reduce fraud losses and duration significantly – firms with reporting mechanisms caught frauds 6 months faster and at half the median loss compared to those without hotlines. Executives must also be alert to behavioural red flags that may indicate collusion. ACFE studies show many fraudsters exhibit warning signs such as living beyond their means or having an unusually close relationship with a vendor or customer. An employee who is overly cosy with a supplier (e.g. always socialising together, or showing reluctance to change a problematic vendor) could be involved in a kickback scheme. Unexplained wealth, secretive behaviour, or unwillingness to share duties are classic red flags of internal conspiracy. Encouraging staff and management to recognise and report these red flags can lead to early detection of collusion.

Data Analytics and Anomaly Detection:

In the digital age, forensic data analytics has become a powerful detective tool to uncover collusion patterns that might escape human notice. Advanced analytics can scan large volumes of transactions to spot anomalies or suspicious patterns suggestive of fraud. For example, data analysis might reveal if an employee and a vendor share the same bank account or address, indicating a fictitious vendor created by an insider. Analytics can also flag repetitive invoice numbers, duplicate payments, or a sudden spike in payments to a little-used supplier – often a sign of a fraudulent vendor scheme. One effective technique is graphing payments over time to each vendor: genuine suppliers usually have steady or business-driven patterns, whereas a collusive fraudulent vendor often shows an acceleration pattern – a few small test payments followed by rapidly increasing amounts once the scheme faces no resistance. By visualising such trends, investigators can pinpoint vendors or accounts that merit closer review. Automated transaction monitoring can drastically shorten the duration of fraud schemes; ACFE reports that organisations using proactive data monitoring cut the median fraud duration to 6 months, versus 12+ months without it. As a best practice, companies should deploy periodic forensic data analytics on high-risk areas (such as accounts payable, procurement, and payroll) to detect signs of internal collusion. Running keyword searches on email communications (for terms like “under the table” or “keep this quiet”) and analysing access logs for unusual system usage can also yield clues.

Internal and External Audits:

Traditional audits, while not primarily aimed at fraud detection, do play a role in uncovering collusion – especially where glaring irregularities exist. In practice, audits (internal or external) were the second-most common detection method in ACFE’s study (about 20% of cases). A vigilant internal audit function can notice if controls are being overridden or if documentation is consistently missing in certain transactions. However, auditors must approach engagements with professional scepticism, recognising that collusion can nullify normal control expectations. Audit standards warn that management override and collusion are always possible, meaning even “clean” audit reports are no guarantee that fraud isn’t occurring. External financial statement auditors in South Africa have a duty to report any reportable irregularities (significant breaches of law or fiduciary duty, which would include fraud) to regulators under the Auditing Profession Act. This legal requirement creates an additional channel by which collusive activities might come to light, albeit often after the fact. That said, many collusion schemes (especially those involving lower-level staff) do not immediately distort the overall financial statements and thus may escape external audit detection. This reinforces the need for dedicated fraud detection efforts, such as forensic audits and tip-off mechanisms, within the organisation.

Surprise Checks and Reviews:

Given that colluders often take steps to cover their tracks, unannounced inspections can catch them off guard. Management can conduct random spot checks on high-risk processes (e.g. a sudden review of all vendor bank detail change forms for proper authorisation, or an impromptu inventory count in a warehouse). Surprise audits of petty cash or expense claims may reveal conspirators who became lax, assuming no one was watching. Collusion sometimes involves falsified documents; forensic techniques like document examination can detect forgeries or alterations if suspicious paperwork is identified. Additionally, managers should be rotated to review each other’s budgets and operations (a form of management review) – this can bring fresh eyes that might question irregular arrangements a collusive group put in place. Whistleblower reports, data analytics, and audits all complement each other. Indeed, ACFE recommends using data analysis to “bolster traditional detection techniques that rely on reactive leads (whistleblower tips, complaints, etc.)”. In summary, to detect internal collusion early, companies should combine a culture of transparency (so that honest employees speak up) with technological and audit-based approaches to scrutinise transactions. The next section discusses what to do when these detection methods indicate collusion – namely, how to investigate thoroughly via a forensic audit.

2. Investigative Processes in Forensic Auditing

When red flags suggest internal collusion, a structured investigative process is essential to confirm the fraud, gather evidence, and identify all parties involved. A forensic audit investigation typically unfolds in several stages: planning, evidence preservation, data analysis, interviews, and reporting. Throughout, it is critical to maintain confidentiality and legal compliance, as the investigation may lead to disciplinary action or criminal prosecution.

Planning and Scope Definition:

Upon suspecting collusion, senior management or the audit committee should promptly engage qualified forensic professionals – either an internal forensic audit team (if available) or external specialists. Often, legal counsel is involved at this early stage to advise on legal considerations and possibly to engage the forensic auditors in a way that communications are protected by legal privilege. The first step is to define the scope and objectives: What transactions or business areas are under suspicion? Which period should be examined? A clear engagement letter is usually drawn up, outlining that the forensic audit will focus on the specific allegations or risk areas (e.g. “investigation of procurement kickback scheme in the IT department for the last three years”). Defining scope prevents scope creep and ensures all stakeholders understand the mandate. However, investigators remain alert to other frauds uncovered in passing – if additional misconduct is discovered, the scope can be expanded with due approval. At the outset, the forensic team will also perform conflict of interest checks to ensure investigators are independent of the suspects and situation. A detailed investigation plan is then developed, including who will be on the team, what records will be collected, what analytics and tests will be performed, and an approximate timeline. It is important to act swiftly to preserve evidence but also discreetly to avoid tipping off suspects prematurely.

Evidence Preservation and Data Collection:

A collusion investigation requires comprehensive evidence gathering from both electronic and physical sources. Investigators will secure relevant financial records (ledgers, invoices, contracts, expense reports, etc.), either by retrieving backups or imaging computers and servers. Digital forensics plays a big role – specialists can take a forensic image of suspects’ hard drives and email accounts to capture all data (even deleted files) without altering the original. It is crucial that only trained forensic IT experts handle this process, to maintain the chain of custody and ensure admissibility of electronic evidence in court. Key communications (emails, messaging logs) between alleged co-conspirators are often treasure troves for proving collusion, so those are high priority to collect. Physical evidence is also considered: forensic auditors might perform an out-of-hours search of a suspect’s office or desk (with proper legal authority) to seize incriminating documents, sticky notes, diaries, or USB drives. All collected evidence is carefully logged – noting who collected it, when, and where it was found – to preserve the chain of custody for each item. Additionally, investigators may secure CCTV footage, telephone records, and access logs if relevant (for instance, to see if suspects met after hours or accessed areas they normally wouldn’t). In some cases, especially with external collusion, public records and OSINT (open-source intelligence) are gathered to trace connections between employees and vendors (common directorships, shared addresses, etc.). This broad evidence collection ensures that collusion, which often leaves an eclectic trail, is captured from all angles.

Forensic Data Analysis:

With data in hand, the forensic audit team conducts in-depth analysis to uncover the mechanics and extent of the collusive scheme. Unlike a regular audit that samples data, a forensic investigation often examines 100% of transactions in the scope, since even small suspicious amounts cannot be dismissed as immaterial. Investigators use specialised software (e.g. IDEA, ACL, or Python scripts) to crunch through financial data, applying techniques such as: sequence gap testing (looking for missing invoice numbers or duplicated cheques), Benford’s Law analysis on numeric fields (to spot artificial patterns in figures), cross-matching employee and vendor master data (to find overlaps as noted earlier), and trend analysis over time. They will reconstruct timelines of events and fund flows – essentially “following the money”. If collusion involves kickbacks, forensic accountants try to quantify how much was paid in bribes or how much the company overpaid due to rigged prices. They also search for proof of agreement between colluders: for example, matching the timing of invoice approvals to personal communications (did an employee text the vendor right before a purchase was approved?), or identifying that multiple suspect transactions share the same approver or originate from the same IP address. In complex cases, link analysis software can be used to visualise relationships between entities (people, bank accounts, companies) to demonstrate the network of collusion. Throughout the analysis, the forensic team keeps an open mind – collusion often spawns various fraudulent acts (false invoices, ghost employees, inventory theft, etc.), so they look holistically at any irregularities. The goal is not only to confirm the initial suspicion but also to uncover the full extent of the conspiracy and any additional schemes. As evidence emerges, the team continuously evaluates if more data or specialist expertise is needed (for instance, a handwriting expert if signatures are disputed, or a database expert if data records seem manipulated). In sum, the data analysis phase of a forensic audit is exhaustive and driven by the maxim: “follow the evidence wherever it leads.” No stone is left unturned if it could illuminate how the collusion operated.

Interviews and Interrogation:

Once substantial documentary evidence has been gathered and analysed, the forensic auditors proceed to interviews. Typically, they start with neutral or peripheral witnesses before moving to core suspects, to gather information and cross-verify stories. Interviews are conducted strategically and discreetly. For example, an investigator might interview a procurement clerk about how a certain vendor was selected, without immediately accusing anyone of fraud – this can yield insights into whether normal procedures were bypassed and by whom. By the time key suspects are interviewed, the investigators usually have a strong fact base from the documents, which can be used to confront lies or inconsistencies. Interviews should be handled by experienced fraud examiners, as suspects in collusion cases may be evasive or attempt to coordinate their answers. Skilled interviewers use open-ended questions and carefully reveal evidence to elicit admissions. It is important to conduct suspect interviews under controlled conditions (often with a second interviewer as a witness) and, if appropriate, with legal or HR representatives present, especially if disciplinary action will result. Sometimes, the mere awareness that a rigorous forensic audit is underway can prompt wrongdoers to confess or cooperate – the psychological pressure of an investigation should not be underestimated. In all interviews, detailed notes or recordings are kept as these may become evidence. If an interviewee reveals new leads (e.g. “Actually, you should look at vendor X, I think they were also involved”), the team will follow up accordingly. Throughout the process, confidentiality is paramount – information is shared on a need-to-know basis to prevent tipping off any not-yet-interviewed suspect.

Collaboration with Law Enforcement and Regulators:

If at any point the investigation uncovers likely criminal conduct (such as bribery, theft, or fraud above certain thresholds), legal counsel will advise on reporting obligations. In South Africa, for instance, the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act (PRECCA) mandates that corruption over R100,000 be reported to police. The forensic audit team should compile evidence in a format digestible by law enforcement, anticipating that criminal charges could follow. In some cases, it may be prudent to involve law enforcement early (for example, to obtain search warrants for external premises or to advise on entrapment operations if the collusion is ongoing). However, the company must balance this with maintaining control of the internal investigation. Close cooperation between the forensic auditors, the company’s counsel, and external agencies ensures that any handover of evidence or coordination (e.g. timing the confrontation of suspects with possible arrests) is handled smoothly. Similarly, if the company is publicly listed or in a regulated industry, regulators might need to be informed of the investigation’s findings in due course.

Reporting and Documentation:

The culmination of a forensic audit is a detailed report outlining the investigation process, evidence, findings, and recommendations. A well-structured forensic report typically includes: (1) an executive summary, (2) background and scope, (3) methodology (what was examined and how), (4) findings – describing each impropriety uncovered, with supporting evidence, (5) quantification of losses or amounts involved, (6) identification of those responsible, and (7) recommendations for action (disciplinary, legal, or control improvements). All key evidence, such as transaction listings or copies of forged documents, is included as exhibits in the report. The report should be factual and avoid speculation – its purpose is to support decision-making by management or the board, and it may be used in court proceedings or internal hearings. Forensic auditors must be prepared to testify as expert witnesses if the case goes to trial, so their documentation of each step (from evidence logs to interview records) must be meticulous to withstand scrutiny. Once the report is delivered, the organisation’s leadership, often in consultation with legal counsel, can determine the appropriate response. We turn next to those response strategies, i.e. what actions management and the board should take once collusion is confirmed by the investigation.

3. Response Strategies and Remediation

Discovering internal collusion is a serious governance crisis that calls for swift and resolute action. How an organisation responds can significantly influence the damage suffered and the message sent to stakeholders. Response strategies generally fall into three areas: taking action against the perpetrators (accountability), engaging with law enforcement/regulators (legal compliance and recovery), and remediating weaknesses (control improvements and cultural change). A strong response demonstrates that the company’s leadership will not tolerate unethical behaviour, thereby upholding the trust of investors, employees, and the public.

Internal Disciplinary Actions:

The first order of business is to stop the bleeding by removing or neutralising those involved in the collusion. Typically, implicated employees are suspended immediately pending further disciplinary procedures to prevent any further access to assets or ability to interfere with evidence. Following due process under labour law, the company should then terminate employees proven to have participated in fraudulent collusion. In a high-profile South African case, when a major IT company (EOH) uncovered collusion and bribery by some executives, the CEO swiftly “purged the ranks” – about eight employees and executives identified as perpetrators were exited from the company. This kind of decisive action contains the risk and shows other staff that wrongdoing has consequences. In parallel, any colluding third parties (vendors, contractors) should be dealt with – contracts can be frozen or terminated, and the individuals declared persona non grata in future dealings. It is also prudent to communicate internally, on a need-to-know basis, that an incident was uncovered and is being addressed, to quell the inevitable rumours and assure honest employees that the issue is being handled. While exact disciplinary steps may vary by jurisdiction and company policy, consistency and fairness are key. All involved, regardless of rank, should face consequences; failing to hold a senior executive accountable, for example, would undermine morale and potentially violate governance duties (directors in SA have fiduciary duties of care and integrity under the Companies Act and common law). The board or audit committee should be kept apprised throughout and may need to oversee actions involving top management.

Legal and Regulatory Engagement:

Collusive fraud often violates not just company policy but also laws – e.g. fraud, corruption, embezzlement, tax evasion, competition law (if price fixing), etc. Consequently, a robust response involves referring the matter to law enforcement and/or regulators as appropriate. In South Africa, directors have a legal obligation to act in the best interests of the company and with due care – covering up a known collusion would breach those duties. Moreover, failing to report certain crimes can itself be an offence (as under PRECCA for corruption). Therefore, once the facts are gathered, the company’s attorneys will usually compile a brief for the police or specialised anti-corruption units. In the EOH example, the company didn’t “sit on the information” – they swiftly reported the wrongdoing to authorities and even initiated criminal charges against the implicated individuals. Such reporting has multiple benefits: it may lead to prosecution (deterring others internally), it fulfils any legal reporting duties, and it signals to stakeholders that the company is not complicit in the misconduct. In many cases, law enforcement action is slow, but the organisation should cooperate fully – providing forensic audit reports, handing over evidence, and making witnesses available. Additionally, if the company is regulated (e.g. a bank, or listed on the stock exchange), regulators will need to be informed. For listed companies, material fraud would likely need to be disclosed to shareholders via stock exchange news service, as it could affect share price. Transparency at this stage is delicate – while too much disclosure can raise legal risks, too little can erode trust if stakeholders later feel information was withheld. The King IV code encourages transparent disclosure of material matters and proactive stakeholder communication in a crisis, balanced with legal advice.

Another legal avenue is civil recovery. The company should evaluate pursuing civil action to recover losses from the perpetrators or any third-party beneficiaries of the fraud. This could involve suing the employees (though they may not have assets to cover large losses) and any external parties that benefited (e.g. a vendor that overcharged in collusion could be sued for damages). Freezing orders and civil attachment of assets can be sought if there’s a chance to claw back significant funds. According to recent ACFE findings, more organisations are choosing to pursue civil remedies against fraudsters (29% of cases in 2022, up from 23% a decade prior). Civil action can sometimes yield insurance claims as well – many firms carry fidelity insurance for employee fraud, which may cover some losses if promptly reported.

Remediation and Strengthening Controls:

Once immediate actions against individuals are underway, the organisation must address the root causes that allowed the collusion to occur. A thorough post-mortem should be conducted, often by the forensic auditors or internal audit, to identify control breakdowns and process gaps. Was there a lack of segregation of duties? Did management override controls or ignore warning signs? Did the culture discourage employees from questioning unethical directives? The answers should inform a remediation plan. For example, if two employees colluded to approve false invoices, the company might implement a stronger approval matrix (requiring dual approvals including one from a higher level) and ensure that the accounts payable system flags any vendor name or address that matches an employee’s details. If bids were rigged, procurement processes can be tightened – e.g. requiring rotating committee members for tender awards, and implementing random audits of awarded contracts. In the wake of its collusion scandal, EOH overhauled its governance structures: it strengthened board oversight (especially the audit and risk committees), revamped policies on bidding and payments, and instituted a new ethics and compliance regime. These changes, combined with leadership’s commitment to an ethical culture, were aimed at preventing a recurrence.

Preventative controls are discussed in detail in the next section, but as part of the immediate response, management should implement quick fixes for any glaring weaknesses. It’s also crucial to document the remedial actions taken and communicate them to stakeholders such as auditors, regulators, and even employees. Shareholders and the public will want assurance that “lessons have been learned” and that the company emerges stronger. King IV underscores the importance of continuous risk management – Principle 11 directs the governing body to ensure effective controls and risk responses are in place to combat fraud and corruption. Thus, a collusion incident should become a case study within the company for improvement. Many organisations also use the incident as an opportunity to refresh employee training on ethics and anti-fraud policies, emphasising the new controls and the non-negotiable stance on integrity.

Communication and Reputation Management:

Executives must carefully manage communications about the collusion incident. Internally, a candid but controlled disclosure to employees can prevent misinformation – for instance, an email from the CEO stating that “an instance of serious misconduct was uncovered, those responsible are no longer with the company, and we have taken steps to prevent this in future.” This can actually boost confidence among the workforce that leadership takes action. Externally, transparency must be weighed against legal constraints. Generally, companies that cooperate openly with investigations and demonstrate accountability fare better in the court of public opinion. In the case study example, EOH took the bold step of sharing its forensic findings publicly and even testifying in the national inquiry into state corruption, which helped reclaim some trust. The message was that the company was a reformed victim of collusion, not a willing participant. In any industry, a strong response strategy will emphasise that the collusion was an unacceptable breach of the company’s values, and that the company is committed to making things right.

In summary, responding to internal collusion requires both a firm hand and a forward-looking plan. Swiftly remove wrongdoers, engage authorities and pursue recovery, and then fix the vulnerabilities that allowed the scheme to thrive. Done correctly, this approach not only addresses the incident at hand but also fortifies the organisation’s governance. We will now explore preventative controls in more depth – the measures that companies can put in place to minimise the risk of collusion taking root in the first place.

4. Preventive Controls to Mitigate Collusion Risk

Preventing internal collusion is far preferable to dealing with its aftermath. While no system can guarantee to foil determined colluders, a strong anti-fraud control environment will significantly deter collusion and increase the likelihood of early detection. Preventative controls should be layered – combining structural safeguards (policies, procedures, segregation of duties), cultural measures (ethics and awareness), and oversight mechanisms (supervision, audits, and data monitoring). King IV emphasises that an ethical organisational culture and effective control frameworks are foundational to good corporate governance. For management and boards, prioritising these controls is an investment in long-term integrity and performance.

Robust Internal Controls and Segregation of Duties:

At the heart of fraud prevention is a well-designed system of internal controls that ensures no single individual has unchecked authority over critical processes. Collusion often arises to defeat a segregation control – for instance, one employee initiates a fraudulent transaction and another approves it. To counter this, duties should be allocated such that collusion becomes harder (requiring more people to be in cahoots, which is less likely). Key processes like procure-to-pay, payroll, cash disbursements, and inventory management should be reviewed for any “single points of failure.” Implement dual approvals for payments above a threshold, separate the vendor setup function from the payment function, and ensure that managers cannot approve their own expenses. Where practical, use system-enforced controls (e.g. the accounting system should prevent the same user from creating and approving a vendor). Regular job rotation and mandatory vacations are also powerful anti-collusion controls – they break continuous ownership of a process and can reveal hidden issues when a new person takes over temporarily. ACFE research shows that organisations with mandatory job rotation or leave policies see 54% lower fraud losses on average. The logic is simple: if an employee cannot cover their tracks uninterruptedly, a collusive scheme is more likely to unravel. Surprise audits, as noted earlier, are another preventative measure; announcing that random checks will occur creates uncertainty in potential fraudsters’ minds. Many companies also enforce an independent review of reconciliations and key reports – for example, having someone outside a department review its monthly bank reconciliations or inventory write-offs can catch anomalies that a colluder inside might try to hide. Control enforcement must be consistent: exceptions or management overrides must be rare and documented. Colluders often exploit complacency or sloppy adherence to controls (e.g. knowing that their boss never really checks the purchase orders when signing). Thus, management must “walk the talk” by following and enforcing control procedures strictly.

Fraud Risk Management Framework:

Leading organisations establish a formal fraud risk management program that continuously evaluates where fraud (including collusion) could occur and implements controls accordingly. This aligns with guidance from the ACFE and principles of King IV which call for a holistic anti-fraud framework. Such a framework might include periodic fraud risk assessments where management identifies scenarios of collusion (for example, “sales rep colludes with customer for kickbacks” or “procurement staff and supplier conspire to inflate prices”) and then assesses the effectiveness of existing controls to prevent each scenario. If gaps are found, new controls are designed. This proactive approach ensures controls keep pace with changes in the business. It may also involve setting up a dedicated fraud risk management committee or assigning a senior executive as fraud risk owner. As part of this framework, clear policies must outline unacceptable conduct (e.g. a strict anti-collusion or conflict-of-interest policy) and the consequences of violations. Employees should be required to declare potential conflicts of interest annually, disclosing any close relationships with suppliers, customers or other employees that could give rise to collusion. If, say, an employee’s brother owns a vendor company, that employee should not be in a position to influence hiring that vendor. Many collusive incidents have occurred because such relationships were hidden. A robust vendor onboarding procedure that includes due diligence (checking ownership, verifying addresses, etc.) can catch attempts to set up shell companies for collusion.

Ethical Culture and Employee Awareness:

Perhaps the strongest preventive weapon is an organisational culture that prizes integrity and makes it clear that fraud will not be tolerated. Tone at the top is crucial – executives and directors must model ethical behaviour and ensure that middle management does the same. King IV explicitly links ethical leadership to improved fraud prevention outcomes. This can be operationalised by incorporating ethics into performance evaluations and promotion criteria (King IV recommends that ethical conduct be considered in performance appraisals). Training and communication are key to building awareness. Regular training sessions (at least annually) on the code of conduct, anti-fraud policy, and practical fraud indicators help keep employees vigilant. Stories of actual fraud cases (anonymised or from public cases) can be shared to illustrate how collusion might look and reinforce that “it can happen here.” ACFE advises that fraud training combined with a strong reporting mechanism greatly increases the likelihood that fraud will be caught internally. When employees are trained to recognise suspicious patterns and know exactly how to report concerns, it creates a hostile environment for colluders. They know their colleagues are watching and willing to speak up. Creating this perception of detection – that fraud will be noticed – is often enough to deter wrongdoing. Incentives also play a role in culture: companies should be careful that their incentive structures do not inadvertently encourage collusive behaviour (for example, overly aggressive sales targets with big commissions might tempt employees to collude with customers on side deals). A balance between performance and ethical process must be maintained.

Whistleblower Protection and Encouragement:

As discussed in the detection section, whistleblowing is critical. From a prevention standpoint, management should actively foster an environment where employees feel safe to voice concerns. This means having not just a hotline, but also clear anti-retaliation policies and demonstrated follow-up on reports. The “duty to inform” provisions in South Africa’s Protected Disclosures Act (as amended in 2017) actually require employers to keep whistleblowers informed about the status of their reports. This helps reporters trust that action is being taken. An effective practice is periodically publicising (in internal newsletters or townhalls) the number of reports received and resolved, or sharing sanitised examples, to show that tips lead to results. When employees see that whistleblowers are thanked – not punished – and that management genuinely wants to hear about problems, the willingness to come forward increases. This early-warning system can stop collusion before it grows. Additionally, some organisations offer rewards (monetary or recognition) for valid whistleblower tips that uncover significant fraud, further incentivising vigilance.

Continuous Monitoring and Technology:

Advances in technology allow companies to implement continuous controls monitoring. For instance, software can continuously scan transactions for pre-defined red flags (like round-dollar payments, or multiple invoices just under approval limits) and alert management in real time. Data analytics, as noted, isn’t just for detection after the fact – it can be embedded into processes to prevent or flag anomalies immediately. For example, an accounts payable system might reject an invoice if it detects a duplicate number, or an HR system might alert if an employee address matches a vendor address. Using artificial intelligence and machine learning, organisations are beginning to predict and identify patterns of collusion by analysing communication networks and behaviour indicators (though this is an emerging field). At a simpler level, even enforcing proper digital access controls helps; ensure that employees only have system access needed for their role, so colluders cannot exploit broad access to perpetrate and then conceal fraud. Regular IT access reviews can catch if, say, a user still has rights that should have been revoked, or an administrator account is being misused – factors that could facilitate collusion.

External Oversight – Audits and Reviews:

Engaging external experts periodically to review anti-fraud controls can provide an objective check. This could be through an external quality assessment of the internal audit function, a focused fraud risk audit by a consulting firm, or requiring the external financial auditors to perform specified procedures on fraud risk areas. King IV suggests that combined assurance (a mix of internal and external assurances) be used to cover key risks, including fraud risks, to ensure nothing falls through the cracks. An external perspective may catch complacency or blind spots that internal teams overlook. Moreover, knowing that independent reviewers might scrutinise transactions serves as another deterrent to collusion.

It’s worth noting that despite best efforts, no control environment is foolproof. Collusion, by definition, subverts controls that rely on checks by another person. Thus, preventative measures aim to make collusion as difficult as possible and to create multiple lines of defense. As a PwC fraud prevention guide aptly notes, most external frauds involve some internal collusion, so companies should always consider the possibility of insider help when designing controls and investigating issues. By continuously reinforcing a culture of ethics, maintaining strong controls, and monitoring diligently, organisations can drastically reduce the opportunities and temptations for collusion. The following case study illustrates many of these concepts by recounting how a South African company identified and addressed a major internal collusion scheme through forensic auditing, and emerged with stronger controls and governance as a result.

5. Case Study: Forensic Audit Uncovers Collusion at EOH

Background:

EOH Holdings, once one of South Africa’s largest technology service companies, became embroiled in a collusion scandal in the late 2010s. It was revealed that a subset of executives and employees at EOH had been involved in corrupt dealings, including bid rigging and kickbacks in government IT contracts. This collusion not only violated company policy but also facilitated large-scale fraud and bribery, putting the organisation’s reputation and finances in peril. The new CEO, appointed in 2018 amid these allegations, decided to initiate a thorough forensic investigation to get to the bottom of the issue and restore trust. The case provides a real-world example of how detecting and addressing internal collusion via forensic audit can save a company from potential ruin.

Detection and Decision to Investigate:

The first signs of trouble came via external whistleblowers and irregularities flagged in due diligence. Rumours swirled that EOH’s public sector arm had secured tenders through illicit payments. Rather than denying problems or doing a cursory internal probe, the board took the proactive step of commissioning an independent forensic audit by a law firm with forensic expertise (ENSafrica). Shareholder pressure and governance best practice (as highlighted by King IV) supported an independent investigation to ensure objectivity. This reflects the Companies Act provision that shareholders (and boards acting for them) can demand a forensic audit when impropriety is suspected. ENSafrica’s forensic team was given a broad mandate – essentially, “find everything and report without fear or favour.” This immediate embrace of a forensic audit exemplifies a strong tone at the top: leadership signalled that ethical conduct was non-negotiable and any collusion would be rooted out transparently.

Investigation and Findings:

Over several months, the forensic auditors combed through years of EOH’s records, focusing on the division dealing with government contracts where suspicions were highest. They traced payments, reviewed contracts and communications, and conducted interviews. The findings were explosive: approximately R1.2 billion (about $80 million) in suspicious transactions were uncovered. These included unsubstantiated payments to consultants and third parties, suggestive of bribery, and tender irregularities such as inexplicably inflated pricing. The forensic audit revealed severe governance failings – essentially that certain managers had overridden controls and colluded to bypass procurement rules. For example, payments were made to shell companies with no evidence of services rendered, indicating pure pay-offs. The issues dated back several years, implicating transactions as far back as 2014. The collusion involved a handful of EOH executives conspiring with outside business partners (and even a government official) to siphon funds. One particularly damaging revelation was that a city official (later a prominent political figure) had received payments funnelled through an intermediary company, pointing to bribery in exchange for city IT contracts. The forensic audit team meticulously traced money flows, even identifying that some illicit payments benefited politically connected individuals – evidence that elevated the issue to national importance. The thoroughness of the investigation meant that by the end, EOH had a clear map of who did what, how they did it, and how much it cost the company.

Response and Consequences:

Armed with the forensic audit’s findings, EOH’s leadership moved swiftly on multiple fronts. First, they cleaned house: employees and executives who were directly involved in the wrongdoing were identified and promptly removed from the company. In fact, even before the final report was out, several implicated executives resigned as the probe closed in. In total, around eight individuals were held mainly responsible and exited – showing that no one, no matter their rank, was above accountability. Next, EOH did not hide the malfeasance – the company publicly disclosed the issues and reported them to law enforcement authorities. ENSafrica’s team assisted EOH in preparing reports for the police and regulatory bodies, and EOH announced it would be pursuing criminal charges against those involved. This proactive cooperation with authorities was critical. It sent a signal to regulators, investors, and clients that EOH was a victim of rogue actors and was taking responsibility to “clean house,” rather than being complicit. Additionally, EOH initiated civil recovery efforts: by October 2019, the company stated it was seeking to recover losses from the perpetrators, and it took legal steps to reclaim stolen funds or assets wherever possible.

The financial impact was significant – EOH had to write down assets and make financial provisions for the losses and the cost of the investigation. In the short term, the company reported heavy losses, partly due to uncovering this fraud. However, this transparency was viewed positively by the market as a necessary “reset.” The company’s stock, which had plummeted during the scandal, stabilised as investors digested that the worst was being addressed. In subsequent years, EOH’s turnaround efforts, bolstered by the credibility gained from the forensic audit, helped it to recover stability slowly. By late 2020, EOH had improved its financial integrity enough that their external auditor (PwC) felt comfortable issuing an unqualified audit opinion – a key milestone indicating restored trust in the company’s reporting.

Preventative Reforms:

Perhaps the most enduring outcome of the forensic audit was the sweeping governance reforms EOH implemented to prevent such collusion from recurring. The board’s audit committee was strengthened, and new independent directors with compliance expertise were added. Internal controls were tightened across the board: policies for bidding on government work were overhauled to require more transparency and oversight, and payment approval processes were given additional checks (for instance, multiple approvers for large disbursements, and greater scrutiny of vendors). A new culture of ethics was driven from the top by the CEO, who instituted “consequence management” – a clear regime that ethical breaches would result in discipline. EOH also invested in ethics training and set up better whistleblowing channels. The case had shown how a lack of questioning and weak controls allowed collusion to fester, so management now encouraged employees to speak up and ask tough questions. EOH’s cooperation with the state’s anti-corruption commission (the Zondo Commission on State Capture) further demonstrated its commitment to transparency. The CEO even testified publicly, using the forensic audit’s findings to detail how the corruption happened, thereby contributing to broader anti-corruption efforts in the country. This move to “air the dirty laundry” was unusual but ultimately helped differentiate EOH as a company that was willing to own up and reform, unlike some peers who stayed defensive.

Outcomes and Lessons:

The EOH case vividly illustrates both the damage collusion can cause and the power of a forensic audit and strong response to contain that damage. By uncovering the full extent of the wrongdoing, EOH’s forensic audit enabled the new management to take precise corrective action – almost like surgically removing a cancer. The company survived a crisis that might have sunk it, had the collusion continued unchecked. EOH’s share price and business gradually stabilised as stakeholders saw that the rot had been cut out and governance was improved. The case also underscored the importance of not being in denial. If EOH’s leadership had tried to downplay the allegations or conduct only a superficial inquiry, the issue could have snowballed, potentially leading to far greater losses or even the collapse of the company. Instead, the willingness to confront ugly truths head-on (a trait King IV would term ethical and effective leadership) proved to be the key to saving the organisation.

From a broader perspective, the EOH saga serves as a cautionary tale and an example of best practice. It demonstrates how internal collusion can infiltrate even large, seemingly well-run companies, especially in environments with high corruption risk. It also shows that proactive forensic auditing is essential in such contexts – had an independent investigation not been done, many of these issues might never have come to light until it was too late. For other executives and boards, the message is clear: when red flags of collusion emerge, act decisively. Engage experts, investigate thoroughly, be transparent, and fix what’s broken. By doing so, a company can emerge from a collusion scandal leaner, cleaner, and more trusted, just as EOH sought to do. This case study reinforces the guidance and strategies discussed in the previous sections, bringing to life the idea that identifying and addressing internal collusion through forensic auditing is not just a theoretical best practice – it is a real-world necessity for safeguarding an organisation’s future.

Conclusion

Internal collusion is a formidable threat, but as this paper has detailed, it can be effectively identified and addressed through vigilant forensic auditing and strong governance responses. In today’s corporate landscape – especially in high-risk environments like South Africa where economic crime rates are elevated – boards and executives have a clear mandate to actively seek out and stop fraud within their organisations. A forensic audit is a powerful instrument in this regard, going far beyond routine checks to reveal the truth behind suspicious activities. By employing a combination of detection methods (from whistleblower systems to data analytics), a thorough investigative process, decisive response strategies, and robust preventative controls, companies can close the gaps that colluders exploit. The tone from the top and adherence to governance frameworks such as King IV are critical enablers – when leadership drives an ethical culture and demands accountability, collusion finds little fertile ground. Conversely, when oversight is lax, even well-crafted controls can be bypassed by colluding insiders.

For corporate management and governance professionals, insights from ACFE and similar bodies offer a roadmap: encourage tips, protect whistleblowers, invest in fraud awareness training, and implement controls such as job rotations, surprise audits, and continuous monitoring to minimise the opportunity for collusion. Importantly, organisations must recognise that simply having controls on paper is not enough – it is the consistent enforcement and the perceived likelihood of detection that truly deters unethical behaviour. As seen in the case study, a proactive stance can turn a potential catastrophe into a story of recovery and improvement. EOH’s experience proved that embracing a forensic investigation and acting on its findings not only averted collapse but also earned back stakeholder confidence over time.

Ultimately, the fight against internal collusion is ongoing. It requires staying one step ahead of fraudsters through vigilance and adaptation. Corporate executives should view resources spent on forensic audits and anti-fraud controls not as an expense, but as an investment in the organisation’s longevity and reputation. As one analysis noted, preventing even a single major fraud can repay these investments many times over, considering the alternative of undetected schemes leading to financial and reputational ruin. Moreover, intangible benefits – like maintaining a culture of integrity, preserving investor trust, and safeguarding the company’s license to operate – are priceless in today’s accountability-focused business environment. In conclusion, identifying and addressing collusion through forensic auditing is both a protective measure and a statement of values. It signals that an organisation is committed to transparency, to justice for wrongdoing, and to continuous improvement of its governance. Such companies not only minimise their fraud losses but also stand out as trustworthy and resilient, even in the face of the ever-evolving risks of collusion and fraud.

Sources:

- ACFE, Occupational Fraud 2022: Report to the Nations – Key findings on detection methods and impact of collusion.

- Duja & Co. (2025), Strategic Value of Forensic Audits for C-Suite Risk Mitigation – Insights on proactive forensic auditing in South Africa.

- King IV Report on Corporate Governance for South Africa – Principles on ethical leadership, fraud risk management, and control environment.

- Barter McKellar Attorneys (2024), Shareholders’ Right to Request a Forensic Audit in South Africa – Explanation of Companies Act provisions for forensic audits.

- ACFE Fraud Magazine – Collusion in the Workplace (Edelman & Owens, 2014) – Case study of internal collusion and control failures.

- ACFE Fraud Magazine – Attacking Bid-Rigging and Collusion (2022) – Use of data analysis to detect collusive schemes.

- Nisivoccia LLP (2023), New ACFE Study: Knowledge is Power – Statistics on hotline effectiveness and internal control improvements.

- PwC Australia (2008), Effective Fraud Investigation – Guidance on forensic techniques and noting internal collusion in external frauds.

- South African Human Rights Commission (2022), Whistleblowers FAQs – Emphasising the importance of whistleblowing in combating corruption.

- EOH Forensic Investigation Outcome (2019) – Public statements and testimony from EOH detailing the findings of collusion and subsequent actions.